2025 was meant to be the year the bull market finally stumbled.

Download PDF VersionNo major economy is in recession, inflation is still falling back from its spike in 2022-23 and central banks have been cutting interest rates. The global economy has also displayed considerable resilience by shrugging off everything that has hit it in recent years. President Trump’s tariffs are the latest dog that didn’t bark and have not derailed the fundamentally benign economic backdrop. Moreover, corporate profits growth is very strong.

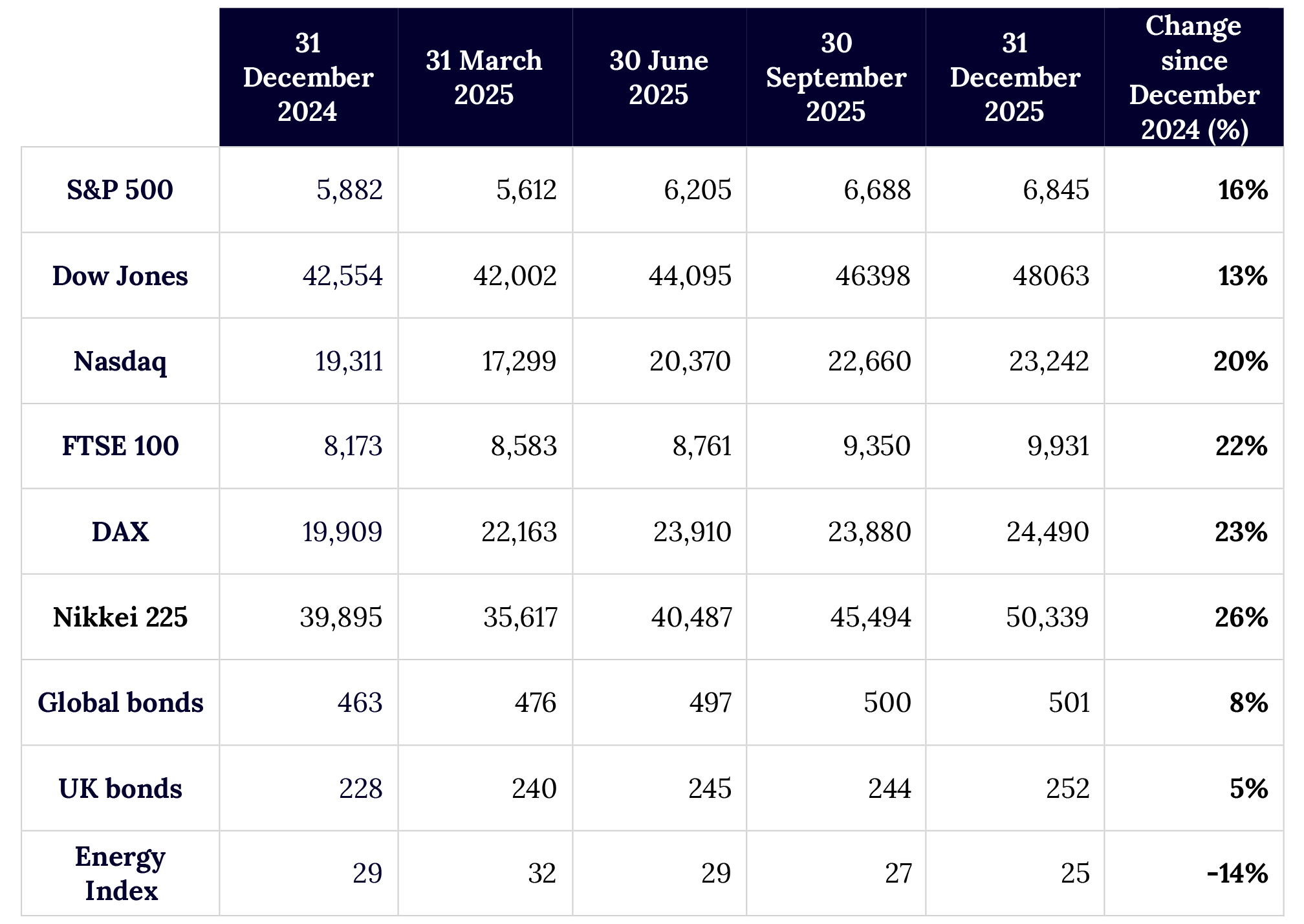

Defying fears about Donald Trump, sluggish economies, and an AI bubble, 2025 proved to be another strong year for stock markets (along with gold and other metals). US technology stocks were not the only game in town. Stock markets in Europe, Japan and many emerging markets outperformed the US in local currency and by even more once the weaker dollar was factored in.

Last quarter, we shifted our market outlook from "cautiously optimistic" to “neutral” on the basis that the optimistic and pessimistic scenarios are now evenly balanced, and are sticking to this view. The most likely scenario for 2026 is more of the same: benign economies, falling inflation and gradual interest rate cuts. The benign state of the global economy has been a critical and underestimated driver of the equity bull market. But there are important risks. Probably the biggest economic risk is a possible pick-up in US inflation, which would throw a spanner in the works by stopping Fed rate cuts and raising long-term bond yields. Another common refrain is that we are in an AI bubble. While we do not believe we are in a bubble, this does not preclude a downturn in technology stocks or the AI story. An upset in another corner of the markets or a geopolitical event are, of course, also possible.

These days there is much talk of an AI bubble and no shortage of experts warning that the current equity bull market is destined to end in much the same way as the dotcom bubble of 1999-2000. It is certainly true that the Nasdaq index has risen inexorably in recent years, doubling since 2023. But this is relatively slow compared to the dotcom boom, when the index doubled in just six months between October 1999 and March 2000.

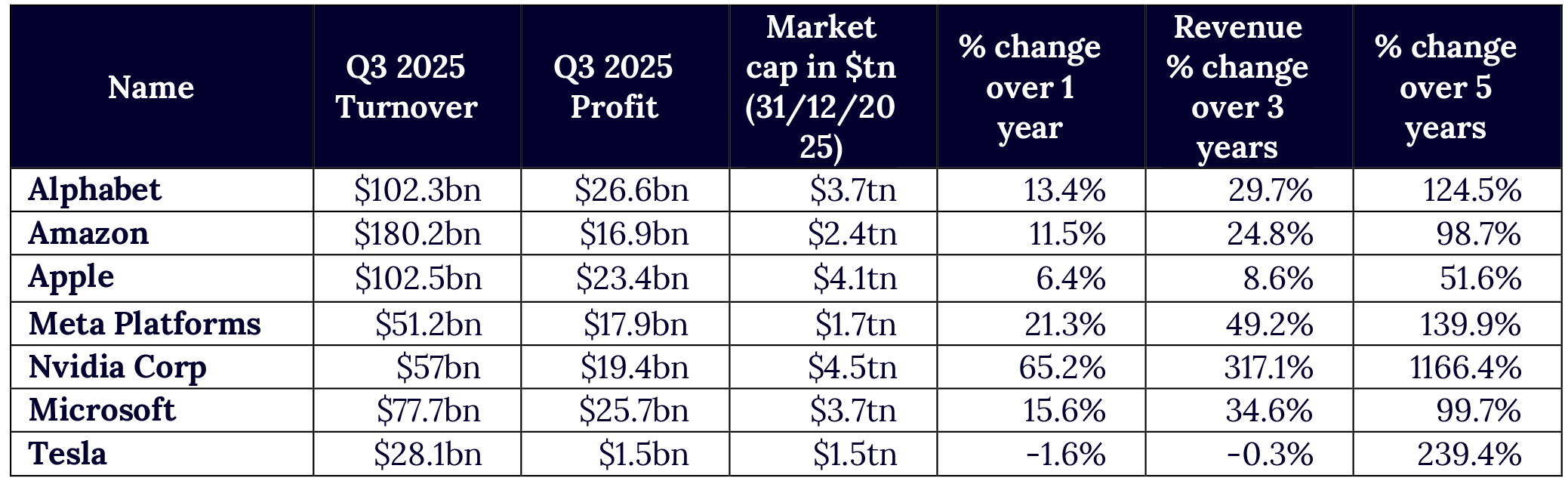

Perhaps the most important difference between then and now is that today’s leading technology companies are all hugely profitable and, in some cases, quasi-monopolies. They are well-run businesses and global leaders in their field. The “hyperscalers” Meta, Microsoft, Alphabet and Amazon can basically afford their huge capital spending on AI infrastructure. If AI were to disappoint as a technology, it would not be life-threatening for them. Moreover, the market has not blindly rewarded all things AI over the past year. In fact it has scrutinised the spending of the technology giants closely and punished those – such as Meta and Oracle – whose capital spending it has judged to be unaffordable. All of the Magnificent 7 technology stocks, apart from Alphabet and Nvidia, actually underperformed the broader market last year (and even Nvidia underperformed in the fourth quarter). Alphabet had a very strong stock-specific story, while Nvidia has a virtual monopoly in the chip that powers a rapidly growing new technology, so it would be surprising if it wasn’t a stock market darling.

Our conclusion is that we are not in an AI bubble and do not face a re-run of the dotcom crash. Which is not to say, of course, that there will not be a correction at some point in technology stocks, either because AI adoption is slower than expected or for other reasons. By their nature such corrections are not pre-announced and are often fast and severe. But a peak-to-trough drawdown of almost 80% like we saw in 2000 to 2002 is highly unlikely in our view.

The debate about whether there is a bubble in US technology stocks and AI is, in one sense, academic, as market downturns are an intrinsic part of equity investing and the market does not need to be in a bubble for there to be a pullback. Hard to believe, but anyone buying Nvidia in late 2021 was sitting on losses of around 60% by October 2022! In spite of the vertiginous since that low point (of around 1,700%) those investors didn’t return to profit until mid-2023, in other words were in loss for around 18 months. Ironically, if there was a market downturn for economic rather than AI-related reasons, technology stocks might actually outperform more economically sensitive stocks and markets.

It was a mixed quarter for US technology stocks. The Nasdaq index was up just 2%, and among the “Magnificent 7”, Meta and Microsoft were down, while only Alphabet performed strongly with a gain of almost 30%. Looking at 2025 as a whole, Alphabet and Nvidia were the standout performers and the other Mag 7 stocks all lagged the broader market to varying degrees. Market movements in the fourth quarter show that the market is very far from uncritically accepting an AI narrative and has punished stocks whose capital spending plans it believes to be excessive (such as Meta and Oracle).

Growth surprises on the upside

The month-long government shutdown in the US led to the cancellation of some economic releases and may have distorted some data. Nonetheless, recent data has painted a picture of an at least stable, if not strengthening, economy and lower-than-expected inflation. Third-quarter US GDP growth surprised on the upside with quarterly growth of 4.3%, following 3.8% in Q2 and 0.5% in Q1. Furthermore, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act will deliver tax rebates to many Americans in the coming months, which should boost consumer spending. If the Supreme Court strikes down some of the president’s tariffs, the administration could be forced to temporarily pay refunds to importers, even if it finds ways to re-impose tariffs through different legislation, potentially boosting the economy even more.

The latest consumer price inflation data for November was better than expected, with headline inflation falling from 3.0% to 2.7% and core inflation from 3.0% to 2.6%. The data is widely believed to be distorted by the shutdown, however, and probably overstates the fall in inflation. The underlying picture is that inflation has shown some persistence and is only converging slowly with the Fed’s target. Tariffs have probably added between 0.5–1 percentage point to headline inflation, but some analysts fear the worst of the tariff impact may be yet to come through, as importers have either been running down stockpiles or absorbing much of the cost until now. The more reliable Personal Consumption Expeditures (PCE) inflation index edged up to 2.8% in September from 2.7% in August; more recent data is not available yet due to the shutdown.

The weakening of the labour market earlier in 2025 led to concerns that this could become a self-sustaining trend and has been one of the justifications for the Fed cutting interest rates. In the event the deterioration has been modest and there are signs it has come to an end (subject to the data shortage due to the government shutdown). The unemployment rate has only ticked up marginally from 4.2% in November 2024 to 4.6% in November 2025. Meanwhile, the JOLTS (job openings and labour turnover) survey has shown private job openings steadying in recent months. The risk that weakness in the labour market could beget further weakness and feed through to consumer spending and other areas of the economy therefore seems to have dissipated for now.

Manufacturing remains one of the softest parts of the economy. With the exception of two months at the start of 2025, the ISM purchasing managers’ index has remarkably been below the expansion/contraction threshold of 50 for over three years. It softened further to 47.9 in December, its weakest reading in 2025. Consumer spending has held up relatively well, however, with retail sales growing at around 4% year-on-year in recent months (around 1% in real terms), although consumer confidence has been persistently weak.

German economy disapppoints

Overall, euro area data has been respectable, with GDP growing by 0.3% quarter-on-quarter in the third quarter and 1.4% year-on year. Retail sales were up 1.5% year-on-year in October, while the unemployment rate was 6.4%, just marginally higher than 6.3% in October 2024. The S&P Eurozone composite Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) stood at 51.5 in December, consistent with a growing eurozone economy. The big disappointment, however, has been Germany. There had been hopes that the loosening of Germany’s debt brake and resultant increased spending on defence and infrastructure would boost German growth, but these hopes have now been pushed out to 2026 and even 2027, as there has been little sign of an economic upturn in 2025. The Ifo business climate index, a reliable leading indicator of the German economy for decades, showed signs of a recovery in the early months of 2025, but stalled in the latter part of the year.

Where Europe differs most markedly from much of the rest of the world is inflation, which is now back on target. Euro area CPI inflation was 2.1% in November, with core inflation at 2.4%.

Welcome signs of a slowdown in inflation

The UK economy remains sluggish. GDP grew by just 0.1% quarter-on-quarter in Q3 and was up 1.3% year-on-year. In a possible irony of Brexit, this was once again almost an identical performance to the euro area.

All parts of the economy are performing in line with this overall sluggish picture. Unemployment has risen by 0.8 percentage points over the past year to 5.1% in October 2025. Retail sales were up just 0.7% year-on-year in real terms in November and are still 3% below the pre-pandemic level of February 2020. One encouraging sign has been a pickup in the S&P manufacturing PMI in the last few months, with the index reaching 50.6 in December, its highest level in 16 months. The services PMI was 51.4 in December, showing modest growth, though it is well below its long-run trend of around 54.

One of the UK's main economic challenges has been its stubbornly high inflation. There was some good news in November, however, with the CPI falling 0.2% on the month for an annual increase of 3.2%, down from 3.6% in October. The services sub-component of the CPI edged down from 4.5% to 4.4%, but remains high, as does wage growth at 4.6% year-on year in October. The encouraging inflation data in November paved the way for the Bank of England’s 25bp rate cut in December, but further progress will be needed, particularly in the sticky components of inflation such as services prices and wages, to permit further cuts.

Welcome to “Sanaenomics” - China remains sluggish

The policies of Japan’s first female prime minister, Sanae Takaichi, have been dubbed “Sanaenomics” in imitation of the pro-growth “Abenomics” espoused by her predecessor Shinzo Abe. The main elements of this policy are expansionary fiscal policy, boosting domestic investment and structural reform. She has already launched a stimulus package and called on the corporate sector to raise wages to combat stagnant living standards due to high inflation.

The Chinese economy remains sluggish and continues to be held back by the ongoing slump in the property sector, with house prices still falling year-on year. Exports have been the sole area of strength. Manufacturing and services PMIs recovered just into the growth zone in December, rising to 50.1 in manufacturing and 50.2 in non-manufacturing. However, retail sales, industrial production and investment have all been weak in recent months.

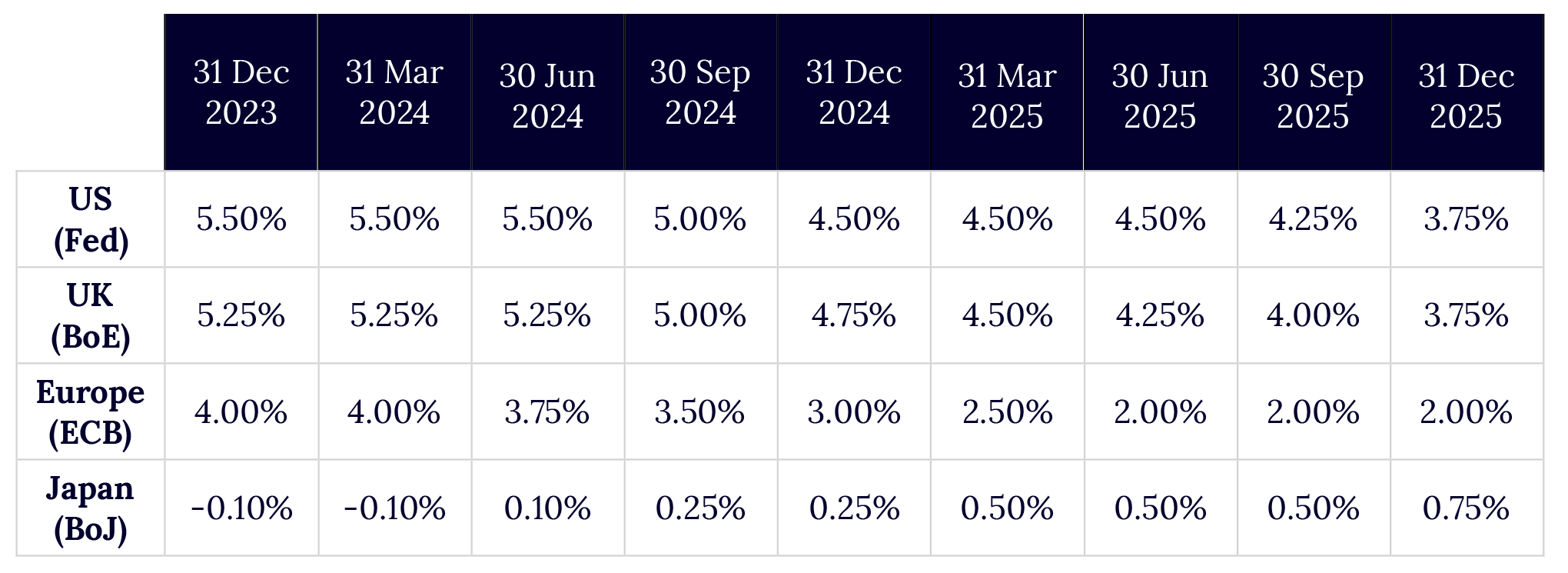

The Fed cut interest rates by 50bp in the fourth quarter to a target range of 3.5–3.75%, which was justified by ongoing softness in the labour market. However, the Fed remains concerned by above-target inflation and the resultant conflict between its dual mandate to keep inflation low while also ensuring maximum employment. At the most recent press conference, Chair Powell implied that the recent rate cuts have been part of the process of “normalisation” that has brought interest rates from a restrictive stance to the neutral range. He also emphasised that monetary policy is not on a preset course. The "dot plot" of the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC's) interest rate forecasts is split, with three FOMC members forecasting that rates will go up by 25 basis points by the end of next year and others forecasting anything from unchanged rates to cuts of up to one percentage point (plus one outlier, presumed to be President Trump’s temporary appointee Stephen Miran, forecasting cuts of 150 basis points).

All of this may become irrelevant when the new Fed chairman takes over in May. President Trump will nominate the successor shortly and the two leading candidates are reported to be Christopher Waller, a fairly mainstream economist who has been a Fed governor since 2020, and Kevin Hassett, a more fringe figure seen as a Trump loyalist through and through. Both have made appropriately dovish statements, however. The president may also have the opportunity to appoint other members of the Federal Reserve Board, which could further tilt the balance towards supporters of much easier policy. It remains to be seen how much pressure the president will exert on the Federal Reserve to slash interest rates. If the economy is performing well, he may decide that it is wiser to keep his hands off it and let the Fed do its job undisturbed.

The European Central Bank (ECB) stayed on hold between October and December for the second quarter in a row, maintaining the discount rate at 2%. Inflation is basically at target, which leaves the ECB in a comfortable position. President Lagarde has indicated that the central bank will take a data-dependent and meeting-by-meeting approach from now on. Theoretically the next interest rate move could therefore be in either direction, though no one is expecting an interest rate hike this year.

The Bank of England trimmed interest rates by another 25bp to 3.75% in December. However, it was a close-run decision, with a majority of just 5–4 in favour of the cut. Although there are hopeful signs, services and wage inflation remain stubbornly high and well above levels consistent with inflation being on target, in spite of the fact that growth has been soft and unemployment edging up for some time. Further sustained improvement in inflation indicators will be needed to allow the Bank of England to lower rates sharply from current levels.

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) raised interest rates by 25 basis points in December to 0.75%. If it had hoped to reverse yen weakness it would have been disappointed, as the market was underwhelmed by the lack of clarity about future rate hikes. The BOJ acknowledges that real interest rates are still negative and it has further to go to normalise monetary policy, but remains cautious about monitoring the impact of higher interest rates on the economy. Prime Minister Takaichi has toned down her opposition to monetary tightening, probably in recognition of the widespread concern in Japan at high and persistent inflation.

The following themes are intended as food for thought and do not represent a formal currency forecast.

Recent trend: neutral

Outlook: ambiguous

Euro/dollar has been stuck in a sideways range at between 1.15 and 1.18 for the last six months. It is likely to break out from this range at some point in 2026. As in 2025, the chief threat to the dollar is a loss of confidence in US policymaking, especially if the market believes the new Fed chair will run an excessively loose monetary policy. Interest rate differentials are less clear-cut. Further Fed rate cuts should narrow rate differentials, as the ECB is now on hold, but this would not necessarily weaken the dollar if rate cuts are seen as reinforcing the strength of the US economy. Conversely, the dollar may not benefit if inflation is higher than expected and the Fed chooses not to cut rates. Overall, the strength of the US economy continues to support the dollar, unless there is an upside surprise on European growth.

Recent trend: neutral

Outlook: neutral to up (weaker dollar)

Sterling/dollar is likely to continue moving in broadly the same direction as euro/dollar, with its fortunes largely dependent on how much the market likes or dislikes US economic policy and the US economy. If the UK finally gets on top of its stubborn inflation problem, allowing the Bank of England to cut interest rates more rapidly, this could lead sterling to strengthen if it leads to a revival in UK growth.

Recent trend: neutral to down

Outlook: neutral to down (stronger sterling)

Interest rate differentials have narrowed in recent months as the Bank of England has cut interest rates while the ECB has stayed on hold. Despite this, sterling has recovered since November. If the recent improvement in UK inflation data is sustained, allowing the Bank of England to reduce interest rates more rapidly and this is seen as boosting the UK economy, sterling could strengthen, in spite of narrowing rate differentials. Conversely, an upturn in the European economy with the prospect of a possible ECB rate increase later in 2026 would benefit the euro.

Our “neutral” outlook on the financial markets implies holding a moderate allocation in all mainstream asset classes. It would not be surprising if non-US and emerging stock markets outperform the US in 2026, just as they did last year. However, if there is a market downturn in 2026, ironically, US markets could outperform (and the dollar might also rise).

The way to deal with market downturns is to hold a well-diversified portfolio that cushions stock market losses and, in most cases, stay invested and await the upturn that inevitably follows in time.

One of the standout assets in 2025 was gold, which rose by a further 65% and is up over 100% over the last two years. As we have highlighted in past quarterly reports, the rally has been driven by a veritable cocktail of concerns, the most potent of which is possibly the weaponisation of the dollar, encouraging central banks to increase their holdings irrespective of price. While it is impossible to call the top for gold, we can be fairly certain that this year’s performance will not be repeated. Although gold remains a valuable hedge, there could be a case for lightening up on holdings or at least not adding at current levels.

Bonds are in some ways the linchpin asset class in 2026. If inflation continues to fall and central banks carry on cutting interest rates, bonds should perform well, but equities would probably remain the best-performing asset class. If, however, there is an inflation disappointment and central banks, particularly the US Federal Reserve, stop cutting interest rates, there could be a sell-off in the bond markets, which could potentially pull the rug from under the equity markets. In these circumstances, bonds would probably outperform equities. A downturn triggered by other risks, such as geopolitics or a market accident, would probably have similar effects.

Stock markets have had another good year. We are now neutral between optimistic and pessimistic views of the future, which implies pegging back risk a little. It is more important than ever to maintain a well-diversified portfolio, maintaining a moderate and geographically diversified exposure to all mainstream asset classes depending on each individual's situation. With our help, constant dialogue with your investment manager is the key to understanding your own risk/reward asset allocation.

Mark Estcourt

CEO